When I was Director of Major Gifts at St. Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis (and later VP for Development and Foundation President), we created something special called the Seton Society. We named it after Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton, who founded the first American congregation of the Sisters of Charity.

Here’s what made it work: We didn’t just recognize donors who gave $10,000 or more—we actually engaged them throughout the entire year. This wasn’t about sending a thank-you note and calling it done. We wanted these donors to feel like true partners in our mission.

How We Kept Donors Engaged All Year

We divided the year into four quarters, and each one offered something different:

-

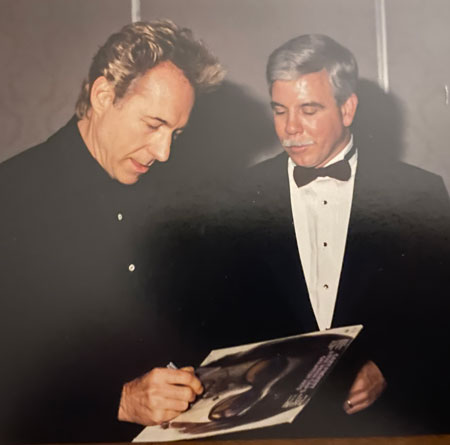

- Winter (Q1): The Celebration We’d host an elegant dinner where each member received something truly personal—an engraved glass bowl designed specifically for them. One donor who loved fishing got a bowl with fishing scenes. A golfer received one with golf motifs. I’ll never forget receiving mine filled with coal—a playful nod to my West Virginia roots. These weren’t just dinners either. We brought in remarkable speakers like Ambassador Andrew Young and entertainers like Johnny Rivers.

-

- Spring (Q2): Rolling Up Our Sleeves This was when members volunteered alongside hospital staff. Real work, real impact. Donors told us they loved getting their hands dirty and seeing firsthand how the hospital operated.

-

- Summer (Q3): Learning Together We organized educational sessions based on what our donors actually wanted to learn about—not just hospital operations, but topics that enriched their lives personally.

-

- Fall (Q4): The Element of Surprise We always saved something unexpected for the final quarter. One year we threw a carnival for members’ families. Another time, we did something completely different. The key was keeping it fresh and memorable.

Click on an image to enlarge.

Keeping It Fresh

Every year, I’d assemble a new committee to plan Society activities. This brought in fresh perspectives and prevented us from falling into predictable patterns. We installed a beautiful plaque in the hospital lobby listing all Society members—visitors couldn’t miss it.

I also led a recruitment team each year to bring in new members. What happened next was remarkable: many Seton Society members eventually joined our Foundation Board. The Society became our leadership pipeline, not just a donor recognition program.

We even created a Volunteer of the Year Award to highlight members who went above and beyond with their time and talents, not just their treasure.

Why It Worked

Looking back, the Seton Society succeeded because we treated donors as whole people, not just checkbooks. That personalized glass bowl? It was just the beginning of a year-long journey where donors felt welcomed, valued, and genuinely part of our hospital family.

The relationships we built through the Seton Society lasted far longer than any single gift. And that was exactly the point.